Note: We’re going to talk in depth about our thoughts while designing this game, which will likely affect your experience of it. We highly recommend playing it first if you have any inclination to do so: Life Game – Childhood & Teenage Years (itch.io)

What is the game about?

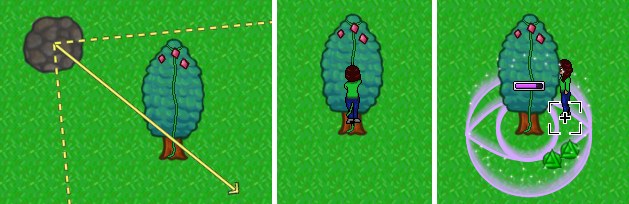

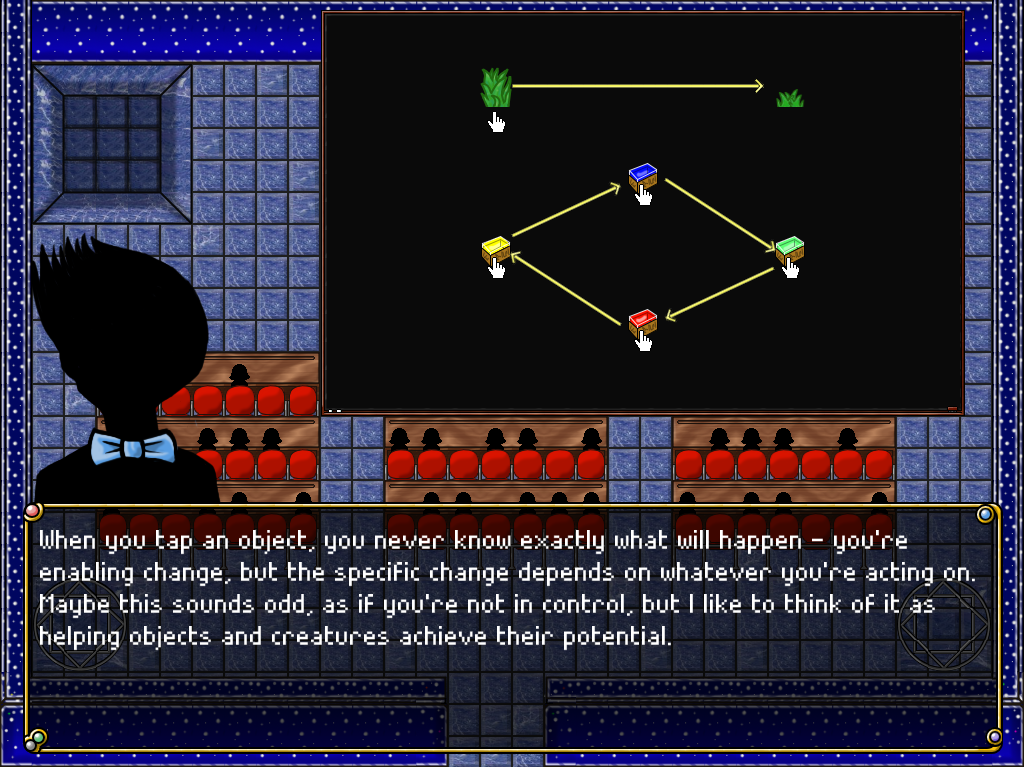

In Life Game: Teenage Years, you play an active role-playing game representing the seven years you spend in Hero Academy, a school preparing magic-wielding individuals like yourself for adulthood and ‘the real world’. While all controls are mouse-based, each of the five magic types has a different way to interact with the world, from moving around to solving puzzles and recharging your energy. With Alteration, you might move in short bursts by tapping in a direction, and solve puzzles by poking everything in sight and seeing what happens. On the other hand, with Force, each move you make counts, as you position yourself by dragging arrows and puzzling out what forces to apply to arrange objects in the world. Your highest stat in Childhood has been brought to Teen in its corresponding magical form, with some links being more obvious (push marbles as a kid, push rocks as a teen), others less so (I Spy becomes an RTS-light called Perception). The Magic stats are now called Music, Perception, Athletics, Force and Alteration.

Each year involves several steps: Lectures, where you learn about your new abilities, Practice, where you can try out new skills and meet your fellow classmates, and Exploration, where you can traverse and interact with the world and level up until classes start up again. Unlike Childhood, each year now takes closer to 15min, and there are seven of them, making 13-20 the years which feel the longest in Life Game. Unfortunately, we never got around to implementing any kind of save system, but you can pause or skip sections when desired.

The RPG structure of the Teenage Years provides more context than the Childhood Years. Actual text gives guidance, and you can solve puzzles and interact with the world for experience to level up. We originally planned to have more structure alongside this, like being able to earn money or even ‘coolness points’ (which we would instantly lose for naming them ‘coolness points’), all of which could provide personal goals while still keeping a ‘do what you want’ atmosphere. Unfortunately, this prototype has only our take on an outdoor nature exploration area, so you’ll just have to use your imagination. We also didn’t get around to implementing end-of-year exams as pseudo-boss battles, for which school children around the world rejoice.

Romy (who worked with us on Dialogue) made all the music and sound effects for the Teenage Years – we’re really glad people will finally get to listen to her songs! Music is a key magic type (and a tricky one to implement, thanks to timings), so we were really glad to have bespoke music for it – the Song of Cheer, Song of Sadness and Song of Wrath.

Thoughts, Goals and Inspirations

Flo: School outlined my life when I was young, so it’s a framing I’m comfortable with for a game, and it’s somewhat universal. Of course, it’s a magical school, so rather than learning history or biology, you’re learning different kinds of magic – but also making friends along the way!

Teen has lots of different inspirations, including Zelda (and Zelda-likes) for their focus on exploration with different abilities, as well as stat-raising school sims. Though I hadn’t played it yet, Magical Diary is the kind of comparison I’d love to draw with this game (I say as someone who has played both Magical Diary games… many times over now). The internet section was inspired by Mega Man Battle Network’s representation of the internet as a physical space. We enjoyed it so much that even though none of the Internet puzzles were implemented, we added the area to the prototype, housing some NPC’s heart-to-heart conversations and its own music.

Speaking of things that didn’t make it in, this game involved a lot of pixel art, including whole zones you won’t be able to see. Pixel art is not the kind of thing I’m most comfortable with, but it’s also sad to have whole sections not see the light of day! Here are a few partial tilesets, so you can enjoy some cute objects/locations.

We wanted people to replay the game, to inhabit different sorts of people, so we encouraged it in a few ways. First were the mechanics. There were more tasks and magic types than one could engage with in one playthrough, so you have to play at least three times to see all the spells, and possibly more to solve all the puzzles (especially since there is more than one solution to every puzzle!). Second were the randomly chosen characters. The player’s avatar and parents are randomly chosen at birth (ie, the start of Childhood), although ‘home’ didn’t get implemented so you never meet your parents. The characters you meet at school were also randomly chosen from a pool, as would have been club members, and the people hanging around the mall or internet.

I wanted to have fellow students who were distinct from one another, but also somewhat flexible in their interpretation. I ended up using silhouettes with one highlighted feature (whose colour corresponds to their favoured magic school). We managed to find space for optional stories with each student, called heart-to-hearts, which lets you get to know them better if you seek them out during the summer holidays. I ended up making 60 character portraits overall!

There were a few themes and ideas we wanted to explore which mostly took place during the final year exams… but these were not yet implemented, just hinted at by the students’ dialogue. We decided to leave exam references in, to add a little intrigue for players, but they’re only the beginnings of what we wanted to express. For example, we wanted to deconstruct the idea of being ‘chosen’ (or ‘a genius’, or ‘special’), ask players to think about the importance of their actions as a teen, and whether the present is more important than the past or future, to question what leads to success or failure (through Teen’s use of randomness, and the NPC’s stories), and individuality (of yourself and the characters, including the inability for any one player to do everything in one run).

Des: Of the three versions of Life Game, Teenage Years was the ‘macro’ out of ‘micro – macro – meta’. It was meant to take the moment to moment interactions of Childhood and give them some context, place them in a world where you could set goals and use those interactions to meet them. Coupled with the growing sense of ‘self’ and personal identity which teenage years often bring, and an abbreviated active RPG felt like a good fit.

Once I knew that’s the direction we wanted, I did what I always do at some point: I asked myself ‘Can I make an RPG… but without combat’ and went from there. Initially there were meant to be more micro activities which would just kind of happen, taking the place of ‘random encounters’, but as the game took shape, there was so much focus on the specific activities and how they could be completed in multiple ways that the other stuff, which was just getting in the way and gumming up the pacing, largely got stripped away to leave a somewhat open space with interactions/puzzles/activities which could often be approached in multiple ways.

There was a lot of iteration on how exactly the different forms of magic worked (and some of them could still definitely use work). There were also some big changes around your ‘energy’ – the stuff you needed to keep on acting in the world. It started as a ‘mana’ bar, which was used whenever you used your magic, which got bigger with levels, and needed refilling by playing a micro-game appropriate to your magic type (a callback to the Childhood). This ended up feeling a bit too restrictive, so it became a ‘biorhythm’ where your movement and actions are more or less impactful depending on how high or low your biorhythm is, and each magic type has different ways of recovering it. I wanted these to be roughly expressive of different people ‘recharging’ in different ways, and while it could be better, I do like how some of it turned out. From the beginning, I was the advocate on the team for Force magic, and Flo was advocate for Alteration magic, and to this day we both still get along with our championed type but get frustrated trying to ‘recharge’ as the other one. I count this as a success.

Like in Childhood, you have some things under your control (what classes you take beyond the first, what you spend your time doing) and some things not (which NPCs appear in your story, how the magic can be used in the world). It was especially difficult to capture something like the pacing of an RPG, but keep it moving. I was resistant to the idea of letting players ‘skip’ sections of time, since I think sometimes interesting and playful things happen when you are plunked in a space with time to kill and your obvious objectives are complete. However, practically it just led to frustration too often, so we added a skip button.

Also as in Childhood, I liked the parallels of the player learning the game while being in a system that wants to teach you things within the fiction of the game (a school). If we needed to explain new mechanics, we could now give the player actual context and instructions in Lectures. If we wanted the player to practise, we could give them a small experimental space in school. Then, we could throw them into a much bigger, less explained space and hopefully let them explore it and poke it as they wish.

We really wanted you to have the option to build basic relationships with characters in this section, so we spent some time distilling down what that might look like in this incredibly simple format. Flo spent a lot of time constructing each character, and I tried to create a design skeleton of ‘opportunities for dialogue’ that we could produce within the confines of the game but went above and beyond npcs-as-signposts, which led to our optional heart-to-heart scene system.